- This event has passed.

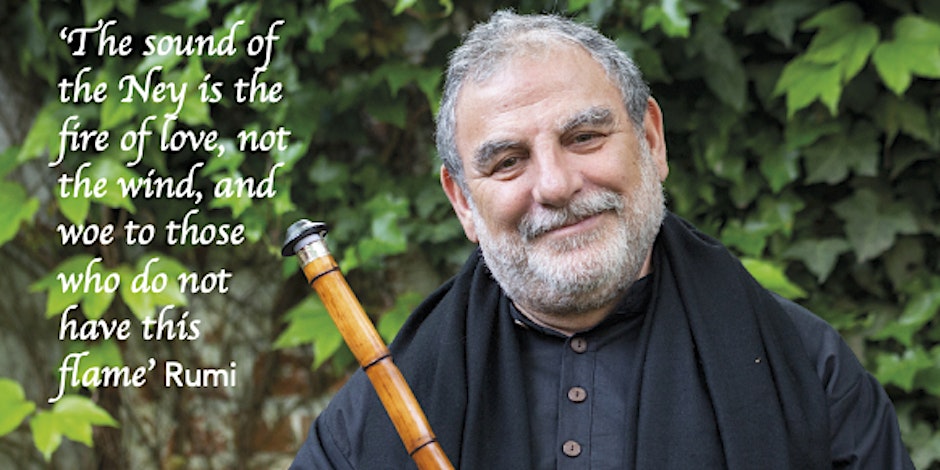

KUDSI ERGUNER MASTER OF THE MEVLEVI NEY

Overview

Ney Master Kudsi Erguner, accompanied on the ud by Tristan Driessen, will perform a concert of sacred hymns and ritual music in remembrance of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (1207–1273), and of all those who, for seven centuries, have traced the luminous path of his teaching. In December 1971, the last spiritual elders of the dervish community brought the Sema to Friends House in London. This rare visitation became an occasion for European scholars and seekers to witness an ancient tradition and to encounter its living custodians. The Sema—an art of profound listening—lies at the origin of the movement that would later be known to the world as the dance of the “Whirling Dervishes”. Kudsi Erguner, who attended those first gatherings as a young ney player beside his father, Ulvi, now offers a Sema shaped for the inward journey.

Kudsi Erguner

Master of the ney, musician, composer, and internationally renowned scholar. Born into a distinguished family of musicians, Kudsi Erguner received a traditional oral transmission of Ottoman classical music from his father, Ulvi Erguner, a master of the ney (reed flute) and a leading figure in Ottoman Sufi music. As the only of his generation to receive such direct training, he absorbed a deep and authentic musical heritage, shaped by centuries of tradition.

Through his participation in various Sufi brotherhood gatherings, Erguner also underwent spiritual and musical training. He took part in the first performances of the Whirling Dervishes’ ceremonies in Europe and the United States, and was a member of the Istanbul Radio Orchestra. In 1973, he moved to Paris, where he studied architecture and musicology, earning both a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree. His concert tours across Europe, the United States, and Japan brought Ottoman classical and Sufi music from Istanbul to Western audiences, raising significant awareness of this rich musical tradition. In Turkey, Erguner formed various ensembles dedicated to reviving neglected and nearly forgotten musical styles, which had been marginalized by the country’s modernist reforms. As an artistic advisor to major festivals, and a record producer for several European labels, he has played a major role in the restoration of these traditions, both internationally and in Turkey. In recognition of his contributions, Erguner was awarded honorary doctorates by Bülent Ecevit University (2014) and Skopje University (2015), and was named UNESCO Artist for Peace in May 2016.

In parallel with his international concert activities, he teaches at CODARTS – University of Performing Arts in Rotterdam. He also founded the Birun Ensemble at

the Cini Foundation in Venice and has led annual masterclasses at the IISMC (Intercultural Institute for Comparative Musical Studies) since 2012

Bibliography

- Journeys of a Sufi musician, translated from French by Anette Courtenay Mayers Saqi books

- The Fountain of Separation, The Book of the Bektashi Dervishes (Bois d’Orion)

- The Mesnevi – 150 Sufi Tales, Rumi and the Whirling Dervishes (with Arzu Erguner, Albin Michel)

- The Flute of Origins (Plon)

- Fifty Misconceptions about Mevlana and Mevlevi Order, Stories from the Mesnevi (alBaraka)

- Ayrılık Çeşmesi, Bir Neyzen İki Derya (İletişim)

- Musiche di Turchia, with Giovanni De Zorzi (Ricordi)

Tristan Driessen

Belgian ud player and composer, Driessen works mainly in the field of Ottoman and early music. He studied makam and ud in Istanbul under his teacher Necati Çelik. He has also collaborated and recorded with master Kudsi Erguner. He holds two master’s degrees, one in musicology (Université Libre de Bruxelles) and one in Turkish ud (Luca School of Arts). He founded the ensemble Lâmekân.

Donations £20 at the door or through Eventbrite / Students £10

(Advanced booking recommended as we expect a full house)

Enquiries only 07887 506848

Refreshments will be served after the event